The Dmitrov Museum in Russia will be holding a conference on Kropotkin. For more information see the poster below or visit their website.

*This has been rearranged from February.

Celebrating the ideas of Peter Kropotkin

The Dmitrov Museum in Russia will be holding a conference on Kropotkin. For more information see the poster below or visit their website.

*This has been rearranged from February.

Had a great time attending the conference organised by Black Rose Books to commemorate the centenary of his death.

In case you missed it, you can re-watch the presentations by clicking the links below:

Continue reading “Relive the Kropotkin Now! International Conference”The long-standing association between anarchism and geography can be traced across the historical landscape from the towering peaks of heightened association to the low valleys of disconnection and ambivalence. Yet if Earth writing is to be understood as “a means of dissipating…prejudices and of creating other feelings more worthy of humanity” (Kropotkin 1978/1885, 7), then it seems obvious that anarchism has much to contribute to the discipline of geography. Geographical writings from influential anarchist philosophers such as Peter Kropotkin and Élisée Reclus blossomed during the late nineteenth century when their work contributed much to the intellectual climate of the time. Following their deaths in the early twentieth century, engagement with their work started to fade, yet the lasting impact of these visionary thinkers continues to be felt within the contemporary geographical theory, influencing the ways geographers think about diverse topics from ethnicity and “race” to social organization and capital accumulation, to urban and regional planning, to environmentalism and, perhaps surprisingly, even anticipating some of the key precepts of the recent “more-than-human” turn. As realpolitik and the quantitative revolution took hold of geography during the war years of the early twentieth century, the anti-authoritarian vision of Reclus and Kropotkin seemed to be pushed beyond the bounds of what were considered to be geographical concerns. Yet, as geographers rediscovered their bearings for social justice in the early 1970s, anarchism came back into the disciplinary view and was afforded serious consideration by academics advocating for what has since become known as “radical geography.” The publication of Antipode announced a new ethic for human geography, one that refused the stochastic models, inferential statistics, and econometrics that dominated geographical proceedings at the time, subverting this trajectory with qualitative approaches that placed the lived experiences of research participants at the center of its methodological focus. Anarchism played a key role in formulating this epistemological critique, where early engagements took inspiration from Kropotkin in arguing that radical geography should adopt his anarcho-communism as its point of departure.

The publication of a special issue of Antipode on anarchism in 1978 demonstrated the ongoinginfluence of anarchist thought and practice on geography, as well as geography’s influence on anarchism. It was not just Kropotkin’s sociospatial contributions to human liberation that were celebrated in the issue, as Reclus also received accolades for the importance of his geographical vision for freedom. A reprinting of Kropotkin’s (1978/1885) essay “What Geography OughtTo Be” was meant to further demonstrate the enduring relevance of his work, while Murray Bookchin’s (1978/1965) “Ecology and Revolutionary Thought” was also reprinted, showing how the anarchism of supposed non-geographers had a significant bearing on the radical geographical thought that was beginning to make itself known. Around the same time, the newsletter of the Union of Socialist Geographers published a themed section on anarchist geographies, arising from a discussion group that took place at the University of Minnesota in 1976. These developments were indicative of a sense of optimism for anarchist ideas to reinvigorate a collective geographical practice that was increasingly turning its attention toward social justice. Yet, as the neoliberalism of the1980s and 1990s began to take hold of the world’s political-economic compass, anarchist engagements by geographers dwindled and were largely overshadowed by Marxist, feminist, and incipient poststructuralist critiques. Nonetheless, the decade of Reaganomics and Thatcherism did see the publication of Bookchin’s (2005/1982)The Ecology of Freedom, wherein he advanced an anarchist critique of nature’s domination by social hierarchy. The beginnings of some introspective reflection on geography’s colonial past and its enduring state-centricity also emerged at that time, where the foundational works of Halford Mackinder, Ellen Churchill Semple, Ellsworth Huntington, Isaiah Bowman, and Thomas Holdich were taken to task by anarchist geographers who drew on Kropotkin and Reclus in calling for the abandonment of our inherited disciplinary prejudices. The 1990sfared slightly better, where a special issue on anarchism was organized for the short-lived journal Contemporary Issues in Geography and Education, while Antipode continued to publish the work of geographers who developed new,anarchist-inspired theories related to counter-hegemonic struggle and resistance to capitalism. More recently a new generation of geographers has begun actively transgressing the frontiers of geography by situating anarchism at the center of their practices, theories, pedagogies, and methodologies, (re)mapping the possibilities of what anarchist perspectives might yet contribute to the discipline (Springer 2013). This anarchist(re)turn comes as capitalism’s house of cards begins to collapse under its own weight, where intensifying neo-liberalization, deepening financial crisis, and the ensuing revolt push anarchist praxis back into widespread currency both inside and outside of the academy.

From the vantage point of the present, it is important to recognize that the reduction in direct engagements with anarchism among academic geographers since the time of Reclus and Kropotkin in no way signals the decline of anarchism as a relevant political idea, something that is now actively being rediscovered by the new batch of anarchist geographers. Instead, it speaks to one of the core tenets of anarchist praxis, centered as it is on the politics of pre-figuration, where anarchism lives through the organization and creation of social relationships that strive to reflect the future society being sought. Prefigurative politics is the recognition that to plan without practice is akin to theory without empirics, history without voices, and geography without context. In other words, pre-figuration actively creates a new society in the shell of the old. So, while academic geography became obsessed with the trappings of positivism, and later the class-centric economism of Marxism, the geography of anarchism simply left the academy for the greener pastures of practice: on the streets as direct action, civil disobedience, and black bloc tactics; in the communes and intentional communities of the cooperative movement; amid activists and a range of small-scale mutual aid groups, networks, and initiatives; as tenant associations, trade unions, and credit unions; online through peer-to-peer filesharing, open-source software, and wikis; among neighbourhoods as autonomous migrant support networks and radical social centers; and, more generally, within the here and now of everyday life. In some ways what we are witnessing today, an even deeper appreciation for anarchism than we’ve ever actually seen within the academy, is the result of a century of struggle. Reclus and Kropotkin were not able to combine their anarchism with their geographical scholarship as they might do today, but not necessarily for lack of trying. Kropotkin was offered an endowed chair at Cambridge University, but turned it down because it came with the stipulation that he give up his political commitments. Nonetheless, the closer we move toward the present moment, the more the literature demonstrates an appreciation for praxis, where the result has been a burgeoning consideration of both sides of the theory/practice divide.

Although anarchism is frequently portrayed as a symptom of mental illness and a synonym for violence and chaos, rather than as a valid political philosophy, such sensationalism is a ploy by its detractors. While violence has informed some historical and contemporary anarchist movements, and it is difficult to deny this constituent, anarchism has no monopoly of violence; compared to other political creeds (e.g., nationalism or monarchism), anarchism is decidedly peaceful. The word “anarchy” comes from the Greek anarkhia meaning “without rule,” or against all forms of “archy” or systems of rule (i.e., patriarchy, oligarchy, monarchy, hierarchy, etc.). Violence can be seen as antithetical to anarchy precisely because all violence involves a form of domination, authority, or rule over other individuals. Violence is thus a particular form of “archy,” and not anarchy at all. Similarly, anarchism refuses chaos by creating new forms of organization that break with hierarchy and embrace egalitarianism. In fact, the symbol for anarchism ‘A’ is meant to suggest that anarchy is the mother of order, an idea advanced by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the first person to identify as an anarchist. Anarchism accordingly represents an unwavering political commitment that seeks to break from hierarchical structures and unfasten the bonds that facilitate and reproduce violence. It is the notion that our shared morality should not be premised on the prejudices of life as it is currently lived through a politics of consensus that is antagonistic toward difference, but rather on a version of empathy that embraces our ultimate integrality to each other and to all that is. Such a process entails the rejection of all the interlocking systems of domination, including capitalism, imperialism, colonialism, neoliberalism, militarism, classism, racism, nationalism, ethnocentrism, sexism, Orientalism, ableism, genderism, ageism, speciesism, homophobia, transphobia, organized religion, and, of course, the state. Simon Springer (2012, 1607) has accordingly defined anarchist geographies as “kaleidoscopic spatialities that allow for multiple, non-hierarchical, and protean connections between autonomous entities, wherein solidarities, bonds, and affinities are voluntarily assembled in opposition to and free from the presence of sovereign violence, predetermined norms, and assigned categories of belonging.” Such a holistic interpretation of anarchist geographies was first laid down by Reclus (1876–1894), whose primary contribution to the discipline was the emancipatory vision detailed in The Earth and Its Inhabitants: The Universal Geography, wherein he conceptualized a coalescence between humanity and the Earth itself. Reclus sought to eliminate all forms of domination, which were to be replaced with love and active compassion between all animals, both human and nonhuman, as a process of humanity discovering deeper emotional meaning through acknowledging itself as but one historical being in the flowering of a greater planetary consciousness. Kropotkin (2008/1902) did much to contribute to such a vision as well with his monumental Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, wherein partial reply to the social Darwinism of his time, he observed mutual aid as cooperation among plants, animals, and humans, including mutual forms of assistance between species, thereby shedding light on a grander sense of agency, foreshadowing recent theorizing within the domain of more-than-human geographies. Anarchist ideas were from the outset explicitly geographical, differing greatly from the industrial imagination of Marxists, as emphasis was placed on decentralized organization, rural life, agriculture, and local production, which allowed for self-sufficiency and removed the ostensible need for central government. Anarchists were also rooted in a view of history that has been confirmed by the anthropological record, where, prior to recorded history, human societies established themselves without formal authority in ways that rejected coercive political institutions. Although early views of anarchism have been critiqued on the basis of their natural-ist assumptions, we would also do well to pause and reflect on the implicit naturalizing of hierarchical structures that suggest that hierarchies necessarily arise as societies grow, rather than analyzing the patterns through which authority is actually constructed and thinking through the innumerable anarchist alternatives that could be and are being developed.

In understanding anarchist geographies, we should begin by noting that anarchism is not about drafting sociopolitical blueprints for the future, nor does it trace a line or provide a model. Prefiguration should not be confused as predetermination, as anarchists are more concerned with identifying social tendencies, where the focus is on the possibilities that can be realized in the here and now. Anarchism accordingly points to a strategy of breaking the chains of coercion and exploitation by encompassing everyday acts of resistance and cooperation, where examples of viable anarchist alternatives are nearly infinite. The only limit to anarchist organizing is our imagination, and the sole existing criterion is that anarchism proceeds nonhierarchically. Such horizontal organization may come in the form of child-care collectives, street parties, gardening clinics, learning networks, flashmobs, community kitchens, free skools, rooftop occupations, freecycling, radical samba, sewing workshops, coordinated monkeywrenching, spontaneous disaster relief, infoshops, volunteer fire brigades, micro radio, building coalitions, collective hacking, wildcat strikes, neighbourhood tool sharing, tenant associations, workplace organizing, knitting collectives, and squatting, which are all anarchism in action, each with decidedly spatial implications. So what forms of action does anarchism take? “All forms,” Kropotkin once answered: “Indeed, the most varied forms, dictated by circumstances, temperament, and the means at disposal. Sometimes tragic, sometimes humorous, but always daring; sometimes collective, some-times purely individual, this policy of action will neglect none of the means at hand, no event of public life, in order to … awaken courage and fan the spirit of revolt.” (2005/1880, 39) Anarchist organization doesn’t seek to replace top-down state mechanisms by standing in for them; rather, it replaces them with people building what they need for themselves, free from coercion or the imposition of authority. Rather than proceeding from a centralized polity, social organization is conceived through local voluntary groupings that maintain autonomy as a decentralized system of self-governed communes of all sizes and degrees that coordinates activities and networks for all possible purposes through free federation. The coercive pyramid of the state structure is replaced with webs of free association, in which individual localities freely pursue their own political-economic and socio-cultural arrangements.

Anarchist geographies are actually not novel, in the sense that people have organized themselves collectively and practised mutual aid to satisfy their own needs throughout human history. Organization under anarchism is simply a continuation of this impulse, despite its attempted disruption by the state. As Colin Ward argued: “given a common need, a collection of people will, by trial and error, by improvisation and experiment, evolve order out of the situation – this order being more durable and more closely related to their needs than any kind of order external authority could provide. “(1982/1973, 28) There is consequently no transgeohistorical narrative to anarchism as, although it has been continuously present in human societies, mutual aid is nonetheless differentiated across space and time, taking on unique and even subtle forms according to context, needs, desires, and constraints placed on reciprocity by opposing systems such as capitalism. At certain times and in particular places mutual aid has been central to social life, while at other times the geographies of mutual aid have remained largely hidden from view, overshadowed by domination, competition, and violence. Yet, irrespective of adversarial conditions, mutual aid remains prevalent, and “the moment we stop insisting on viewing all forms of action only by their function in reproducing larger, total, forms of inequality of power, we will also be able to see that anarchist social relations and non-alienated forms of action are all around us.” (Graeber 2004, 76)

It is in the spirit of seeking new forms of organization that anarchist geographies have been “reanimated” as of late (Springer et al . 2012), emphasizing a do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos of autonomy, direct action, radical democracy, andnoncommodification. Arguments in favour of the radical potential of DIY culture have emphasized anarchist perspectives toward the everyday trans-formation of our lives, a sentiment that factors heavily in a great number of social movements, where geographers have begun thinking through how impermanent spaces may arise in response to sociopolitical action that eludes the formal structures of hierarchical control. Pickerill and Chatteron (2006) have adopted such an “autonomous geographies” approach in attempting to think through how spectacular protest and everyday life may be productively combined to enable alternatives to capitalism. Routledge’s (2003) notion of “convergence space” has similarly proven influential to anarchists insofar as it appreciates how grassroots networks and activists come together through multiscalar political action to produce a relational ethics of struggle, offering a reconvened sense of nonhierarchical organization.

The application of an explicitly anarcho-geographical perspective would benefit a range of contemporary issues, each with decidedly spatial implications, from the overt uprisings of the Arab Spring and the Occupy movement, to the spectacle of street theatre and Critical Mass rides, to the subversive resistance of trespassing and culture jamming, to lifestyle choices of dumpster diving and unschooling, to the mutual aid activities of community gardens and housing co-ops, to the organizing capabilities of bookfairs and Indymedia. Similarly, anarchism has much to contribute to enhancing geographical theory, where it is easy to envision how new research insights and agendas might productively arise from taking an anarchist approach to themes such as sovereignty and the state; homelessness and housing; environmental justice and sustainability; industrial restructuring and labour geographies; capital accumulation and property relations; policing and critical legal geographies; informal economies and livelihoods; urban design and aesthetics; agrarian transformation and landlessness; nonrepresentational theory and more-than-human geographies; activism and social justice; geographies of debt and economic crisis; belonging and place-based politics; participation and community planning; biopolitics and governmentality; postcolonial and post-development geographies; situated knowledges and alternative epistemologies; and anti-oppressive education and critical pedagogy. Kropotkin viewed teaching geography as an exercise in intellectual emancipation insofar as it afforded a means not only to awaken people to the harmonies of nature, but also to dissipate their nationalist and racist prejudices, a promise that geography still holds, and one that may be more fully realized should anarchist geographies be given the attention and care that is required for them to blossom. Retaining Reclus’s and Kropotkin’s skepticism for and challenges to the dominant ideologies of the day has much to offer contemporary geographical scholarship and its largely unreflexive acceptance of the civilizational, legal, and capitalist discourses that converge around the state. The perpetuation of the idea that human organization necessitates the formation of states is writ large in a discipline that has derided the “territorial trap,” yet has been generally hesitant to take the critique of state-centricity in the direction of anarchism. However, unlike the limited class-centricity of Marxian geography, the promise of anarchist geographies resides in their integrality, which refuses to assign priority to any one of the multiple dominating apparatuses, because all are seen as irreducible to one another. This means that no single struggle can wait on any other, and the a priori privilege of the workers, the vanguards, or any other category over any other should be rejected on the basis of its incipient hierarchy. Anarchism is quite simply the struggle against all forms of oppression and exploitation, a protean and multivariate process that is decidedly geographical. Anarchism is happening all about us.

Bookchin, M. 1978. “Ecology and RevolutionaryThought.” Antipode, 10: 21. (Original work published in 1965.)

Bookchin, M. 2005. The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy. Oakland, CA: AKPress. (Original work published in 1982.)

Graeber, D. 2004. Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Kropotkin, P. 1978. “What Geography Ought ToBe.” Antipode, 10: 6–15. (Original work published in 1885.)

Kropotkin, P. 2005. “The Spirit of Revolt.” In Kropotkin’s Revolutionary Pamphlets, edited by R.Baldwin, 34–44. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger. (Original work published in 1880.)

Kropotkin, P. 2008. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. Charleston, SC: Forgotten Books. (Original work published in 2002.)

Pickerill, J., and P. Chatterton. 2006. “Notes towards Autonomous Geographies: Creation Resistance and Self-Management as Survival Tactics.” Progress in Human Geography, 30: 730–746.

Reclus, E. 1876–1894. The Earth and Its Inhabitants: The Universal Geography. London: J.S. Virtue.

Routledge, P. 2003. “Convergence Space: ProcessGeographies of Grassroots Globalization Net-works.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 28: 333–349.

Springer, S. 2012. “Anarchism! What Geography StillOught To Be.” Antipode, 44: 1605–1624.

Springer, S. 2013. “Anarchism and Geography: A Brief Genealogy of Anarchist Geographies”

1842 December 21 – Peter Alekseyevich Kropotkin is born in Moscow. The fourth child of parents Major General Prince Alexei Petrovich Kropotkin and Ekaterina Nikolaevna Kropotkina.

1846 April 29 – Ekaterina Kropotkina dies of consumption at the age of 34.

1855 March 2 – Death of Nicholas I.

1857-1862 – Begins studying at the Page Corps, a military academy, in St. Petersburg.

1861 – Emancipation of the serfs. Also the year where Kropotkin has his first paper published in the journal Book Bulletin, a review of the essay ‘Working proletariat in England and France’ by Shelgunov.

1862 July 6 – Departs St. Petersburg for Siberia to serve with the Amur Cossacks.

1863 January – January uprising in Poland against Russian rule.

1863 June-September – First trip along the Amur river.

1864 – Geographical expedition to Manchuria.

1865 – Two Trips to Manchuria in 1864 published and received a positive reception.

1865 May-June – Expedition to the Sayan Mountains returning along the Oka river valley.

1865 August-December – Sailing expedition along the Amur and Ussuri.

1865 December – Submits first report to the Russian Geographical Society.

1866 – Geological expedition along Lena River as well as trips to Olekminsk and Vitim.

1867 April – Leaves the military and departs Siberia for St. Petersburg.

1867 September – Admitted to St. Petersburg University in the mathematical department but spends most of his time working on geographical matters.

1871 July-September – Exploration of traces of ancient glaciation in Finland and Sweden. Also offered the position of secretary to the Society but declines.

1871 October 6 – His father Alexei Petrovich Kropotkin dies.

1872 – Travels to Switzerland where he joins the Workingmens International Association and spends time with the Jura Federation.

1872 May – Joins the Circle of Tchaikovsky, a literary and revolutionary group.

1873 – Growing literary and academic success continues with the publication of the General outline of the orography of Eastern Siberia with a map and Report on the Olekminsk-Vitim expedition with a map and drawings.

1874 April 4 – Arrested and imprisoned at the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg and placed in cell No. 52.

1875 October – Given permission by the King to continue working on his latest book, about the glacial formation in Sweden and Finland, while in prison.

1876 July 11 – Escape from prison hospital.

1876 August-September – Arrives in England after travelling through Scandinavia. Eventually settles in London and continues writing having several articles published in Nature.

1877 – Moves to Switzerland and travels through Spain and France.

1878 October 8 – Marriage to Sofia Grigorievna Ananyeva-Rabinovich.

1879 April – First issue of Le Révolté is published in Geneva.

1881 March 13 – Alexander II assassinated.

1881 – Expelled from Switzerland.

1881 July – Attends the International Anarchist Congress in London

1882 December 22 – Arrested in Thonon, France.

1883 January – Trialed in Lyon on the charge of being a member of the International.

1883 March – Transferred to Clairvaux prison.

1883 – Continues to write during this troubled year. Has pieces published in Nineteenth Century Magazine and Encyclopedia Britannica.

1885 – Friend and mentor E. Reclus publishes Speeches of a Rebel, a collection of articles by Kropotkin.

1886 January – Released from Clairvaux prison and moves to England, eventually resettling in London.

1886 – Founds the journal Freedom alongside Charlotte Wilson. In Russian and French Prisons is published.

1886 July 25 – His brother Alexander commits suicide in Tomsk.

1887 – Birth of daughter Alexandra.

1890 – Continues to be a prolific essayist, featuring prominently in journals such as the Nineteenth Century. The first essay of what would eventually become the book Mutual Aid is published.

1891 – Anarchist Communism: It’s basis and principles is published.

1892 – La Conquête du Pain (The Conquest of Bread) is first published in French. The Spirit of Revolt is published.

1893 – Elected as a member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

1896 – An Appeal to the Young is published.

1899 – Fields, Factories and Workshops and Memoirs of a Revolutionist are published.

1901 – Travels and gives lectures through the US and Canada. Modern Science and Anarchism is published.

1902 – Memoirs of a Revolutionist is published in Russia and Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution is published in England.

1903 – Helps found a Russian anarchist journal called Bread and Liberty.

1905 – Russian Revolution of 1905 (First Russian Revolution). Russian Literature is published.

1906 – Conquest of Bread is published in English. First collected works are published in Russia but publication would soon be discontinued because of censorship.

1907 – Gives a speech to the Royal Geographical Socety of London on ‘The Drying of Eurasia’.

1909 – Publication of The Great French Revolution in French, English and German.

1910 – Anarchism is published in Encyclopedia Britannica.

1911 – Moves to Brighton, England.

1913 – Moves to Switzerland and publication in France of Modern Science and Anarchy.

1914-1917 – Vehemently opposes Germany and spends time during the war giving speeches against Germany and the importance of fighting against them.

1917 February – Russian Revolution

1917 June 12 – Returns to Russia.

1917 August – Moves to Moscow.

1917 October – October Revolution which sees Bolsheviks claim power.

1918 July – Moves to Dmitrov, a town 40 miles north of Moscow.

1919 – Gives lectures throughout the year as well as meeting with Lenin.

1921 February 8 – Peter Kropotkin dies in Dmitrov, Moscow at the age of 78.

1921 February 13 – Funeral of Kropotkin. Lenin personal approves a funeral to which a reported 30,000 people attend and which would be the last mass gathering of anarchists allowed in the Soviet Union.

Memoirs of a Revolutionist, Kropotkin

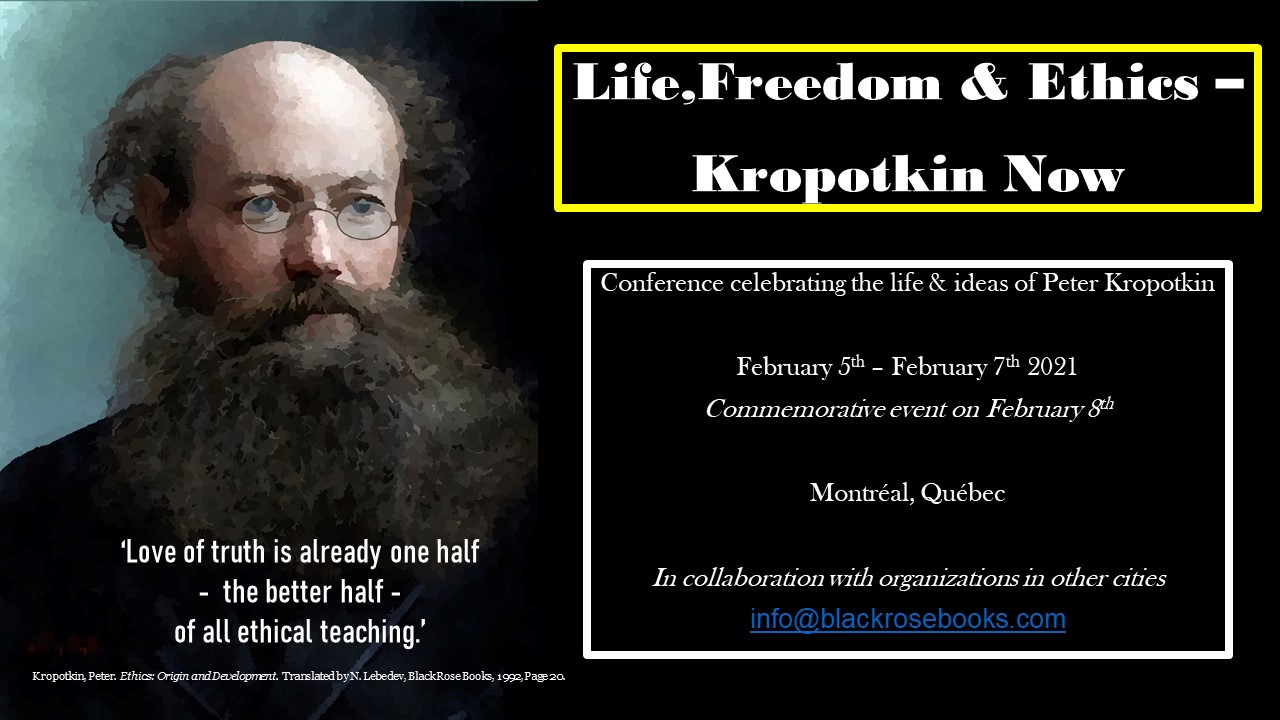

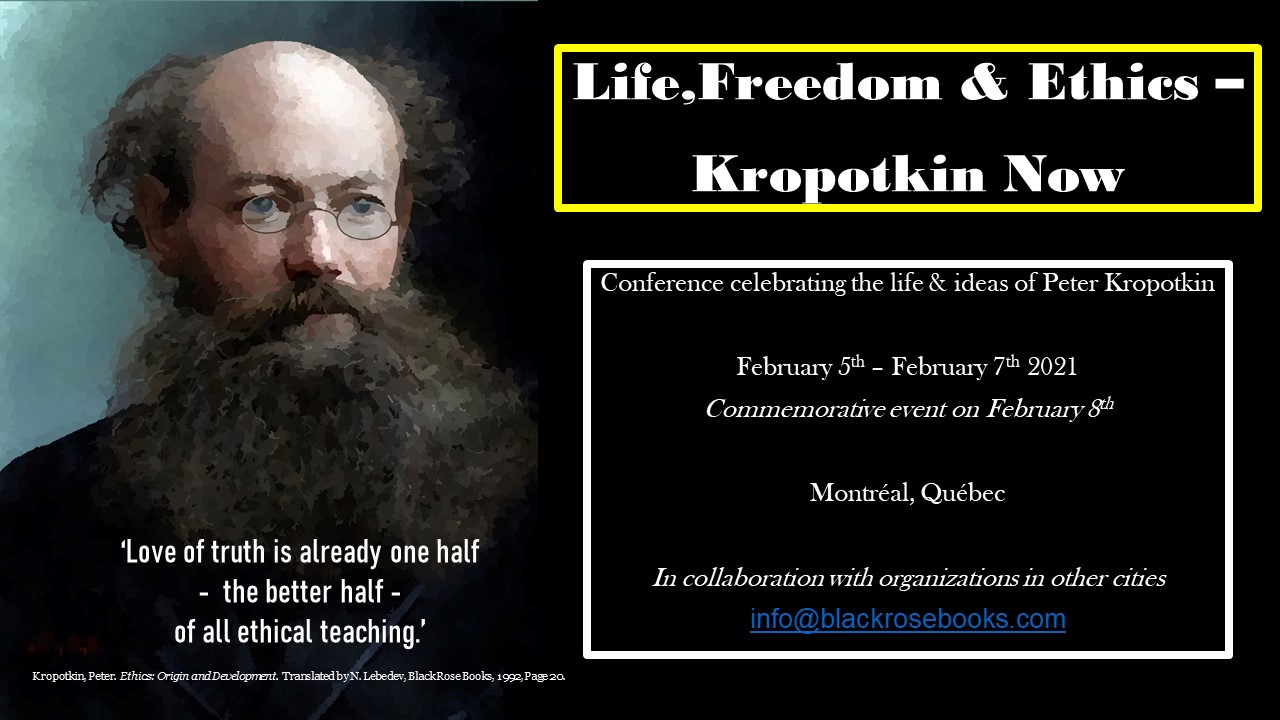

Black Rose Books, in global collaboration with other organisations, scholars, activists and university departments, is organizing a conference to celebrate Peter Kropotkin’s life and work. This conference would commemorate 100 years since his death on February 8th, 1921.

For more information click here

The following message to British workers, by Peter Kropotkin, was brought from Russia by Miss Margaret Bondfield, a member of the British Labour Delegation, who visited him at his home at Dmitrov, near Moscow. His criticism of Soviet rule and his appeal to the workers to stop the war against Russia will be read with interest.

It first appeared in Freedom July 1920

I have been asked whether I have not some message to send to the working men of the Western world? Surely, there is much to say about the current events in Russia, and much to learn from them. The message might be long. But I shall indicate only some main points.

First of all, the working men of the civilised world and their friends in the other classes ought to induce their Governments entirely to abandon the idea of an armed intervention in the affairs of Russia— whether open or disguised, whether military or in the shape of subventions to different nations.

Russia is now living through a revolution of the same depth and the same importance as the British nation underwent in 1639-1648, and France in 1789-1794; and every nation should refuse to play the shameful part that Great Britain, Prussia, Austria, and Russia played during the French Revolution.

Moreover, it must be kept in view that the Russian Revolution— while it is trying to build up a society where the whole produce of the joint efforts of Labour, technical skill and scientific knowledge should go entirely to the Commonwealth itself—is not a mere accident in the struggle of different parties. It is something that has been prepared by nearly a century of Communist and Socialist propaganda, since the times of Robert Owen, Saint-Simon, and Fourier; and although the attempt at introducing the new society by means of the dictatorship of one party is apparently doomed to be a failure, it nevertheless must be recognised that the Revolution has already introduced into our everyday life new conceptions about the rights of Labour, its true position in society, and the duties of every citizen, which have come to stay.

Altogether, not only the working men, but all the progressive elements of the civilised nations ought to put a stop to the support hitherto given to the opponents of the Revolution. Not that there should be nothing to oppose in the methods of the Bolshevist Government! Far from that! But because every armed intervention of a foreign Power necessarily results in a reinforcement of the dictatorial tendencies of the rulers, and paralyses the efforts of those Russians who are ready to aid Russia, independently of the Government, in the reconstruction of its life on new lines.

The evils naturally inherent in party dictatorship have thus been increased by the war conditions under which this party maintained itself. The state of war has been an excuse for strengthening the dictatorial methods of the party, as well as its tendency to centralise every detail of life in the hands of the Government, with the result that immense branches of the usual activities of the nation have been brought to a standstill. The natural evils of State Communism are thus increased tenfold under the excuse that all misfortunes of our life are due to the intervention of foreigners.

Besides, I must also mention that a military intervention of the Allies, if it is continued, will certainly develop in Russia a bitter feeling against the Western nations, and this will some day be utilised by their enemies in possible future conflicts. Such a bitterness is already developing.

In short, it is high time that the West-European nations should enter into direct relations with the Russian nation. And in this direction you—the working classes and the advanced portions of all nations—ought to have your say.

One word more about the general question. A renewal of relations between the European and American nations and Russia certainly must not mean the admission of a supremacy of the Russian nation over those nationalities of which the empire of the Russian Tsars was composed. Imperial Russia is dead, and will not return to life. The future of the various provinces of which the empire was composed lies in the direction of a great Federation. The natural territories of the different parts of that Federation are quite distinct for those of us who are acquainted with the history of Russia, its ethnography, and its economic life; and all attempts to bring the constituent parts of the Russian Empire—Finland, the Baltic Provinces, Lithuania, the Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, Siberia, and so on—under one central rule are surely doomed to failure. The future of what was the Russian Empire is in the direction of a Federation of independent units. It would, therefore, be in the interest of all that the Western nations should declare beforehand that they are recognising the right of self-government for every portion of what was once the Russian Empire.

As to my own views on the subject, they go still further. I see the coming, in a near future, of a time when every portion of that Federation will itself be a federation of free rural communes and free cities; and I believe still that portions of Western Europe will soon take the lead in that direction.

Now, as regards our present economical and political situation—the Russian Revolution being a continuation of the two great Revolutions in England and in France—Russia is trying now to make a step in advance of where France stopped, when it came to realise in life what was described then as real equality (egalite de fait), that is economical equality.

Unfortunately, the attempt to make that step has been undertaken in Russia under the strongly-centralised Dictatorship of one party—the Social Democratic Maximalists; and the attempt was made on the lines taken in the utterly Centralist and Jacobinist conspiracy of Babeuf. About this attempt I am bound frankly to tell you that, in my opinion, the attempt to build up a Communist Republic on the lines of strongly-centralised State Communism under the iron rule of the Dictatorship of a party is ending in a failure. We learn in Russia how Communism cannot be introduced, even though the populations, sick of the old regime, opposed no active resistance to the experiment made by the new rulers.

The idea of Soviets, that is, of Labour and Peasant Councils, first promoted during the attempted revolution of 1905 and immediately realised by the revolution of February, 1917, as soon as the Tsar’s regime broke down—the idea of such councils controlling the political and economical life of the country is a grand idea. The more so as it leads necessarily to the idea of these Councils being composed of all those who take a real part in the production of national wealth by their own personal effort.

But so long as a country is governed by the dictatorship of a party, the Labour and Peasant Councils evidently lose all their significance. They are reduced to the passive role played in times past by “General States” and Parliaments, when they were convoked by the King and had to oppose an all-powerful King’s Council.

A Labour Council ceases to be a free and valuable adviser when there is no free Press in the country, and we have been in this position for nearly two years, the excuse for such conditions being the state of war. More than that, the Peasant and Labour Councils lose all their significance when no free electoral agitation precedes the elections, and the elections are made under the pressure of party dictatorship. Of course, the usual excuse is that a dictatorial rule was unavoidable as a means of combatting the old regime. But such a rule evidently becomes a formidable drawback as soon as the Revolution proceeds towards the building up of a new society on a new economic basis: it becomes a death sentence on the new construction.

The ways to be followed for overthrowing an already weakened Government and taking its place are well known from history, old and modern. But when it comes to build up quite new forms of life—especially new forms of production and exchange—without having any examples to imitate; when everything has to be worked out by men on the spot, then an all-powerful centralised Government which undertakes to supply every inhabitant with every lamp-glass and every match to light the lamp proves absolutely incapable of doing that through its functionaries, no matter how countless they may be—it becomes a nuisance. It develops such a formidable bureaucracy that the French bureaucratic system, which requires the intervention of forty functionaries to sell a tree felled by a storm on a public road, becomes a trifle in comparison. This is what we now learn in Russia. And this is what you, the working men of the West, can and must avoid by ail means, since you care for the success of a social reconstruction, and sent here your delegates to see how a Social Revolution works in real life.

The immense constructive work that is required from a Social Revolution cannot be accomplished by a central Government, even if it had to guide it in its work something more substantial than a few Socialist and Anarchist booklets. It requires the knowledge, the brains, and the willing collaboration of a mass of local and specialised forces, which alone can cope with the diversity of economical problems in their local aspects. To sweep away that collaboration and to trust to the genius of party dictators is to destroy all the independent nuclei, such as Trade Unions (called in Russia “Professional Unions”) and the local distributive Co-operative organisations—turning them into bureaucratic organs of the party, as is being done now. But this is the way not to accomplish the Revolution; the way to render its realisation impossible. And this is why I consider it my duty earnestly to warn you from taking such a line of action.

Imperialist conquerors of all nationalities may desire that the populations of the ex-empire of Russia should remain in miserable economic conditions as long as possible, and thus be doomed to supply Western and Middle Europe with raw stuffs, while the Western manufacturers, producing manufactured goods, should cash all the benefits that the population of Russia might otherwise obtain from their work. But the working classes of Europe and America, and the intellectual nuclei of these countries, surely understand that only by the force of conquest could they keep Russia in that subordinate condition. At the same time, the sympathies with which our Revolution was met all over Europe and America show that you were happy to greet in Russia a new member of the international comradeship of nations. And you surely soon see that it is in the interest of the workers of all the world that Russia should issue as soon as possible from the conditions that paralyse now her development.

A few words more. The last war has inaugurated new conditions of life in the civilised world. Socialism is sure to make considerable progress, and new forms of a more independent life surely will be soon worked out on the lines of local political independence and free scope in social reconstruction, either in a pacific way, or by revolutionary means if the intelligent portions of the civilised nations do not join in the task of an unavoidable reconstruction.

But the success of this reconstruction will depend to a great extent upon the possibility of a close co-operation of the different nations. For this co operation the labouring classes of all nations must be closely united, and for that purpose the idea of a great International of all working men of the world must be renewed; not in the shape of a Union directed by one single party, as was the case in the Second International, and is again in the Third. Such Unions have, of course, full reason to exist, but besides them and uniting them all ‘there must be a Union of all the Trade Unions of the world—of all those who produce the wealth of the world—united, in order to free the production of the world from its present enslavement to Capital.

This was a lecture given by Kropotkin to the Eugenics Congress in London in August 1911. It first appeared in written form in Mother Earth no. 10 December 1912, pg. 354-357

Permit me to make a few remarks: one concerning the papers read by Professor Loria and Professor Kellogg, and another of a more general character concerning the purposes and the limitations of Eugenics.

First of all I must express my gratitude to Professor Loria and to Professor Kellogg for having widened the discussion about the great question which we all have at heart—the prevention of the deterioration and the improvement of the human race by maintaining in purity the common stock of inheritance of mankind.

Granting the possibility of artificial selection in the human race, Professor Loria asks: “Upon which criterion are we going to make the selection?” Here we touch upon the most substantial point of Eugenics and of this Congress. I came this morning with the intention of expressing my deep regret to see the narrow point of view from which Eugenics has been treated up till now, excluding from our discussions all this vast domain where Eugenics comes in contact with social hygiene. This exclusion has already produced an unfavorable impression upon a number of thinking men in this country, and I fear that this impression may be reflected upon science altogether. Happily enough the two papers I just mentioned came to widen the field of our discussions.

Before science is enabled to give us any advice as to the measures to be taken for the improvement of the human race, it has to cover first with its researches a very wide field. Instead of that we have been asked to discuss not the foundations of a science which has still to be worked out, but a number of practical measures, some of which are of a legislative character. Conclusions were already drawn from a science before its very elements had been established.

Thus we have been asked to sanction, after a very rapid examination, marriage certificates, Malthusianism, the notification of certain contagious diseases, and especially the sterilization of the individuals who may be considered as undesirables.

I do not lose sight of the words of our president, who indicated the necessity-of concentrating our attention upon the heredity aspects of this portion of social hygiene; but I maintain that by systematically avoiding considerations about the influence of surroundings upon the soundness of what is transmitted by heredity, the Congress conveys an entirely false idea of both Genetics and Eugenics. To use the word a la mode, it risks the “sterilization” of its own discussions. In fact, such a separation between surroundings and inheritance is impossible, as we just saw from Professor Kellogg’s paper, which has shown us how futile it is to proceed with Eugenic measures when such immensely powerful agencies, like war and poverty, are at work to counteract them.

Another point of importance is this. Science, that is, the sum total of scientific opinion, does not consider that all we have to do is to pay a compliment to that part of human nature which induces man to take the part of the weak ones, and then to act in the opposite direction. Charles Darwin knew that the birds which used to bring fish from a great distance to feed one of their blind fellows were also a part of Nature, and, as he told us in “Descent of Man,” such facts of mutual support were the chief element for the preservation of the race; because, such facts of benevolence nurture the sociable instinct, and without that instinct not one single race could survive in the struggle for life against the hostile forces of Nature.

My time is short, so I take only one question out of those which we have discussed: Have we had any serious discussion of the Report of the American Breeders’ Association, which advocated sterilization? Have we had any serious analysis of the vague statements of that Report about the physiological and mental effects of the sterilization of the feeble-minded and prisoners? Were any objections raised when this sterilization was represented as a powerful deterring means against certain sexual crimes?

In my opinion, Professor McDonnell was quite right when he made the remark that it was untimely to talk of such measures at the time when the criminologists themselves are coming to the conclusion that the criminal is “a manufactured product,” a product of society itself. He stood on the firm ground of modern science. I have given in my book on Prisons some striking facts, taken from my own close observation of prison life from the inside, and I might produce still more striking facts to show how sexual aberrations, described by Krafft Ebing, are often the results of prison nurture, and how the germs of that sort of criminality, if they were present in the prisoner, were always aggravated by imprisonment.

But to create or aggravate this sort of perversion in our prisons, and then to punish it by the measures advocated at this Congress, is surely one of the greatest crimes. It kills all faith in justice, it destroys all sense of mutual obligation between society and the individual. It attacks the race solidarity—the best arm of the human race in its struggle for life.

Before granting to society the right of sterilization of persons affected by disease, the feeble-minded, the unsuccessful in life, the .epileptics (by the way, the Russian writer you so much admire at this moment, Dostoyevsky, was an epileptic), is it not our holy duty carefully to study the social roots and causes of these diseases?

When children sleep to the age of twelve and fifteen in the same room as their parents, they will show the effects of early sexual awakenings with all its consequences. You cannot combat such widely spread effects by sterilization. Just now 100,000 children have been in need of food in consequence of a social conflict. Is it not the duty of Eugenics to study the effects of a prolonged privation of food upon the generation that was submitted to such a calamity?

Destroy the slums, build healthy dwellings, abolish that promiscuity between children and full-grown people, and be not afraid, as you often are now, of “making Socialism”; remember that to pave the streets, to bring a supply of water to a city, is already what they call to “make Socialism”; and you will have improved the germ plasm of the next generation much more than you might have done by any amount of sterilization.

And then, once these questions have been raised, don’t you think that the question as to who are the unfit must necessarily come to the front? Who, indeed? The workers or the idlers? The women of the people, who suckle their children themselves, or the ladies who are unfit for maternity because they cannot perform all the duties of a mother? Those who produce degenerates in the slums, or those who produce degenerates in palaces?

The essay first appeared in Mother Earth no. 5, July 1906

THE Russian Revolution has lately entered into a new phase. Dark gloom hung about the country during the months of January to April. Now it is all bright hopes owing to the unexpected results of the Duma elections all turning in favor of the Radicals. But before speaking of the new hopes, let us cast a glance on that terrible gloomy period which the country has just lived through.

In every revolution, a number of local uprisings is always required to prepare the great successful effort of the people. So it has been in Russia. We have had the local uprisings at Moscow, in the Baltic provinces, in the Caucasus and in the villages of Central Russia. And each of these uprisings, remaining local, was followed by a terrible repression.

The General Strike, declared at Moscow in January last, did not succeed. The working men had suffered too much during the great General Strike in October, 1905, and the partial strikes which followed. And when the provocations of the Government compelled the Moscow workingmen to strike, the movement did not generalize. Only a few factories on the Presnya and a few railway lines joined it. The Grand Trunk—Moscow to St. Petersburg—continued to work, and troops were brought on it to Moscow.

As to the troops stationed at Moscow itself they showed signs of deep discontent, and probably would have sided with the people if the strike had been general and a crowd of 300,000 workingmen had flooded the streets, as they did flood in October last. But when they saw that the General Strike had failed they obeyed their commanders.

And yet the week during which a handful of armed revolutionists—less than 2,000—and the workers on strike in the Presnya fought against the artillery and the soldiers, and when several miles of barricades were built by the crowd—by the man and the boy in the street— this week proved how wrong were all the “fire-side revolutionists” when they proclaimed the impossibility of street warfare in a revolution.

As to the Letts and the Eslhonians in the Baltic provinces, their uprising against their haughty and rapacious German landlords was a great movement. All over a large country the peasants and the artisans of the small towns rose up. They nominated their own municipalities, they sent away the German judges, refused to work for the landlords, paid no rents,—proceeded in short as if they were free. And if their uprising was finally drowned in blood, it has shown at least what the peasants must do all over Russia. In fact the latent insurrection continues still.

The repression which followed the uprising was terrible. The British press has not told one-tenth of the atrocities which were committed by the imperial troops in the Baltic provinces, along the Moscow to Kazan railway line, in the Caucasus, in Siberia, or in the Russian villages. And when we tried to tell the truth about these atrocities, either in some widely read English review, or before large public meetings, we always felt the dead wall of some inexplicable opposition rising against us. The treaty or agreement which has been concluded a few days ago between the Governments of Great Britain and Russia explains now the cause of the opposition to the divulgation in this country of facts which were openly published in the Russian papers, in Russia itself.

The repression was a story of a wholesale murder, accomplished by the troops systematically, in cold blood. Modern history knows only one similarly savage repression : the wholesale murders by the middle-class army at Paris after the defeat of the Commune, in May, 1871. And yet these murders were committed after a fierce fight, in the lurid light of burning Paris.

The detachment of the guard which was sent along the Moscow-Kazan line had not one single shot fired against it. The revolutionists had already left the line and disbanded when that regiment came. But at every station Colonel Minn, head of this detachment, and his officers shot from ten to thirty men, simply taking their names from lists supplied to the troops by the secret police. They shot them without any simulation of a trial, or even of identification. They shot them in batches, without any warning. Shot anyhow, from behind, into the heap. Colonel Minn shot them simply with his revolver.

As to the peasants in the Baltic provinces it was still worse. Whole villages were flogged. Those men whom a local landlord would name as “dangerous” were shot on the spot, without any further inquiries—very often a son for his father, one brother for another, an Ivanovsky for an Ivanitsky. It was such an orgy of flogging and killing that a young officer, having himself executed several men in this way, shot himself next day when he realized what he had done.

In Siberia, in the Caucasus, the horrors were even more revolting. And in five villages of Russia, where the peasants had shown signs of unrest, the same executions went on, sometimes with unimaginable cruelty, as was, for instance, the case in Tamboff, with that governor’s aid, Luzhenovsky, whom the heroic girl Spirido- nova killed. “When I came to the villages and saw the old men who had grown insane after having been tortured under the whips, and when I had spoken to the mother of the girl who had flung herself into the well after the Cossacks had violated her, I felt that life was impossible so long as that man, Luzhenovsky, would go on unpunished.” Thus spoke this heroic girl on her trial.

But worse than that was in store. All the world has shuddered when it learned the tortures to which Miss Spiridonova was submitted by the police officer Zhdanoff and the Cossack officer Abramoff after her arrest. The tortures of our Montjuich comrades and brothers fade before the sufferings which were inflicted upon this girl. And all over Russia there was lately a sigh of satisfaction when that Abramoff was killed and the revolutionist who killed that beast made his escape, and again the other day when it was known that the other beast, Zhdanoff, had met the same fate.

The gloominess which prevailed in Russia when the Witte-Durnovo ministry had inaugurated the wholesale shooting of the rebels could not be described without quoting pages from the Russian newspapers. Over 70,000 people were arrested; the prisons were full to overflowing. Batches of exiles began to be sent, as of old, by mere order of the Administration, to Siberia. The old exiles, returning under the amnesty of November 2, 1905, meeting on their way home the batches of the Witte-Durnovo exiles. The revolutionists of all sections of the Socialist party, Revolutionary Socialists, Anarchists, and even Social Democrats, took to revolver and bomb, and every day one could read in the Russian papers that one, two, or more functionaries of the Crown had been killed by the revolutionists in revenge for the atrocities they had committed. Scores of men and women, like Spiridonova, the sisters Izmailovitch, and so many other heroic women and young men, felt sick of life under such a system of Asiatic rule, and made the vow of taking revenge upon the executioners.

It was under such conditions that the elections to the Duma took place. And now the few supporters of the Tsar had to discover that their satraps had overdone the oppression. Various measures were taken by the Government to manipulate the elections so as to have a crushing majority in their favor. The Liberal candidates were arrested’ the meetings forbidden, the newspapers confiscated—every governor of a province acting as a Persian satrape on his own responsibility. Those who spoke or went about for the advanced candidates were most unceremoniously searched and sent to jail. . . . And all that was—labor lost!

The reaction had developed within these three months such a bitter hatred against the Government that none but opposition candidates had any chance of being listened to and elected. “Are you against these wild beasts or for them?” This was the only question that was asked.

And the Constitutional Democrats obtained a crushing majority in the Duma (pronounce Dooma), such a majority that the Russian Government is now perplexed as to what is to be done next.

The Revolutionary Socialists and the Social Democrats abstained from taking any part in the elections, and therefore there are very few avowed Socialists in the Duma. [9] But apart from that the Duma contains all those middle- class Radicals whose names have come to the front during the last thirty years as foes of autocracy.

The most interesting element in the Duma are the peasants, who have nearly 120 representatives elected. With the exception of some thirty men, who are of unsettled opinion, the peasant representatives are absolutely and entirely with the most advanced Radicals in political matters, and with the Socialist workingmen in all the labor demands. But, in addition to that, they put forward the great question—the greatest of our century—the land question.

“No one who does not till the land himself has any right to the land. Only those who work on it with their own hands, and every one of those who does so, must have access to the land. The land is the nation’s property, and the nation must dispose of it according to its needs.” This is their opinion—their faith, and no economists of any camp will shake it.

“Eighty years ago we were settled in these prairies,” one of those peasants said the other day. That land was a desert. “We have made the value of all this region; but half of it was taken by the landlords (in accordance with the law, of course; but we, peasants, do not admit that a law could be a law once it is unjust). It was taken by the landlords—we must have it back.”

“But if you take that land, and there are other villages in the neighborhood which have no land but their poor allotments, what then?”

“Then they have a right to it, just as we have. But not the landlords!”

There is all the Social Question, all the Socialist wisdom, in these plain words.

“If the peasants seize the land, then the factory hands will apply the same reasoning to the factories!” exclaim the terrified correspondents of the English papers in reporting such plain talk.

Yes, they will. Undoubtedly they will. They must. Because, if they don’t do it all our civilization must go to wreck and ruin—like the Roman, the Greek, the Egyptian, the Babylonian civilizations went to the ground. Another important feature. The Russian peasants don’t trust their representatives. These men from the plough have understood the gist of parliamentarism better than those who have grown infected gradually by Parliament worship. Their election fell upon this or that man; but they knew they must not trust him. Election is somewhat of a piece of gambling. And therefore a number of private peasant delegates are now seen in the galleries of the Russian Duma, whom their villages have sent to keep watch over their representatives in Parliament. They know that these representatives will soon be spoiled and bribed one way or another. So they sent delegates—mostly old, respected peasants, not fine in words, not of the self-advertising class, men who never would be elected, but who will honestly keep their eye upon the M.P.’s.

However, although the Duma has been only a few days together, a general feeling grows in Russia that all this electioneering is not yet the proper thing. “What can the Duma do?” they ask all over Russia. “If the Government doesn’t want it they will send it away. How can 500 men resist the Government if they make up their minds to send them back to their homes?”

And so, all over Russia the feeling grows that the Parliament and its debates are not the right thing yet. It is only a preliminary to something else which is to come. “They will express our needs; they will agree upon certain things” . . . but a feeling grows in Russia that the action will have to come from the people.

And the underground work, the slow work of maturing convictions and of grouping together, goes on all over Russia as a preparation to something infinitely more important than all the debates of the Duma.

They don’t even pronounce the name of this more important thing. Perhaps most of them don’t know its name. But we know it and we may tell it. It is the Revolution: the only real remedy for the redress of wrongs.

This article first appeared in Mother Earth no. 7 September 1907, pg. 277-283

THE dismissal of the second Duma terminated the first period of the Russian Revolution, the Period of Illusions. These illusions were born when Nicholas II., appalled by the general strike of October, 1905, issued a manifesto promising to convoke the representatives of the people and to rule with their aid.

Everyone clearly recollects the circumstances under which these concessions were wrested. Industrial, commercial and administrative activities came to a sudden stop. Neither revolutionists, nor political parties instigated and organized this grand manifestation of the people’s will. It originated in Moscow and rapidly spread over entire Russia, like those great elemental popular movements that occasionally seize upon millions, making them act in the same direction, with amazing unanimity, thereby performing miracles.

Mills and factories were closed, railroad traffic was interrupted; food products accumulated in huge masses on way-stations and could not reach the towns where the populace were starving. Darkness and silence of the grave struck terror into the hearts of the rulers who were ignorant of the happenings in the interior, as the strike had extended to the postal and telegraph service.

It was animal fear for himself and his own that forced Nicholas II. to yield to Witte’s exhortations and convoke the Duma. It was terror before the throng of 300,000 invading the streets of St. Petersburg, and preparing to storm the prisons, that compelled him to concede an amnesty.

It would seem that no faith should have been placed in the faint traces of constitutional liberties thus extorted. The experience of history, especially that of ’48, has shown that constitutions granted from above were worthless, unless a substantial victory, won by the spilling of blood, converted the paper concessions into actual gains, and unless the people themselves widened their rights by commencing, of their own accord, a reconstruction along the lines of local autonomy.

The rulers, who had submitted on the spur of the moment, in such cases have usually allowed the heat and triumph of the people to subside, meanwhile preparing faithful troops, listing the agitators to be arrested or annihilated, and in a few months have repudiated their promises, and forcibly put down the people in revenge for the fear and humiliations they had to undergo.

Russia had suffered so much during the preceding half-century of hunger and outrage and insolence of her masters; Russian cultured society was so exhausted by the long sanguinary and unequal struggle—that the first surrender of the treacherous Romanoff was hailed as bona fide concession. Russia exultingly ushered in the Era of Liberty.

In a previous article we had pointed out that on the very day the October manifesto was signed, introducing a liberal regime, the wicked and treacherous Nicholas, with his consorts, instituted the secret government of Trepoff in Peterhoff, with the object of counteracting and paralyzing those reforms. In the first days of popular jubilations, when the people believed the Tsar, the gendarmerie, under the guidance of the secret government, hastily issued proclamations inciting to slaughter of Jews and intelligents, despatched its agents to organize pogroms and raids. These agents gathered bands of Hooligans, cut down intelligents in Tver and Tomsk, mowed down men, women and children celebrating the advent of freedom, while Trepoff—the right hand of the Tsar—issued the order “not to spare ammunition” in dispersing popular demonstrations.

The majority divined the source of the pogroms. But our radicals had committed their customary blunder. They were so little informed (and are yet to-day) as to the doings in the ruling circles that this double-faced policy of Nicholas was positively known only seven or eight months later when exposed by Urusoff in the first Duma. Even then, prompted by Russian good nature, men still reiterated that it was not the Tsar’s fault, but his advisers’. The Tsar, it was said, was too mild to be crafty. In reality—and it is now becoming a conviction —he is too malicious not to be treacherous.

While the secret government of Peterhof was thus organizing pogroms and massacres, and turning loose upon the peasantry hordes of Cossacks brutalized in their police service, our radicals and Socialists had their dreams of “parliament,” forming parliamentary parties, with their inevitable intrigues and factional dissensions, and imagined themselves in possession of the constitutional procedure that had taken England centuries to form.

The outlying provinces alone understood that, utilizing the discomfiture of the government caught unawares, it was necessary to rise at once, and, without consulting the abortive “autocratic constitution,” to pull down the local institutions which are the mainstay of the government over the entire extent of Russia. Such risings broke out in Livonia, Guria, Western Grusia, and on the East-Siberian railway. The Gurians and Letts set a fine example of a popular insurrection: their first step was to establish local revolutionary autonomy.

Unfortunately these revolts found no support either from their neighbors, or from Central Russia and Poland. And even where the villages revolted in Central Russia they were not sustained by the cities and towns. Russia did not do what was done in July, 1789, when the insurgent town populaces of Eastern France abolished the crumbling-down municipalities, and, acting from below, began with the organization of districts, ordering the town affairs without waiting for royal or parliamentary laws. Even the Moscow rising did not awaken active aid in the masses and failed to put forth the usual revolutionary expedient—an autonomous municipal commune.

Diligent inculcation of German ideals of imperial centralization, of party discipline, into the minds of Russian revolutionists bore fruit. Our revolutionaries heroically joined in the struggle, but failed to produce revolutionary mottoes. Even if they were vaguely surmised there was no one to formulate them definitely.

The individual revolts were crushed. Trains carrying the Semenoff regiment were allowed to pass to Moscow while the revolutionaries were awaiting “directions” from some source. The punitive detachment led by Meller-Zokomelsky left Cheliabinsk and reached Chita unmolested: in spite of the strike on the Siberian railway it was permitted to proceed! The brutal inroads of Orloff raged in the Baltic provinces, but the Letts could elicit no help from the West and Poland. Guria was laid waste, and wherever the Russian peasants stirred the Cossacks beat them down with a ferocity like that of the Terrible Ivan’s bodyguard.

In the meantime the naive—foolishly naive—faith in the Duma was still alive. Not that the Duma was regarded as a check to arbitrariness, or capable in its narrow sphere of curbing the zeal of the Peterhofers. O, no! The Duma was looked upon as the future citadel of legality. Why? “Because,” reiterated our simpleminded intelligents, “autocracy cannot subsist without a loan, and foreign bankers will lend no money without the Duma’s sanction.” This was asserted at a time when the French and even the English governments were backing a new loan, not without guarantees to be sure, for it was desired to draw Russia into a contemplated conflict with Germany.*

Even the dismissal of the first Duma and the drumhead courts-martial did not sober our simple-hearted politicians. They still believed in the magic power of the Duma and in the possibility of gaimng a constitution through it. The character of the labors of both Dumas shows this.

There are words—”winged words”—that travel around the earth, inspire people, steel them to fight, to brave death. If the Duma did not pass a solitary law tending to renovate life, one might at least expect to hear such words. In a revolutionary epoch, when destructive work precedes constructive efforts, bursts of enthusiasm possess marvelous power. Words, mottoes, are mightier than a passed law, for the latter is sure to be a compromise between the spirit of the Future and the decayed Past.

The Versailles House of 1789 lived in unison with Paris; they reacted upon each other. The poor of Paris would not have revolted on the I4th of July had not the Third Estate, three weeks before, uttered its pledge not to disperse until the entire order of things was altered. What if this oath were theatrical; what if, as we now know, had not Paris risen, the deputies would have meekly departed, as did our Duma. Those were words, but they were words that inspired France, inspired the world. And when the House formulated and announced “The Rights of Man,” the revolutionary shock of the new Era thrilled the world.

Similarly we know now that the French King would have vetoed any law about the alienation, even with recompense, of the landlords’ feudal rights; moreover, the House itself (like our cadets) would not have passed it. What of that? Nevertheless, the House uttered a mighty summons in the first article of the declaration of prin

As if Turkey, ten times bankrupt, did not procure new loans, even for war purposes. As if the Western bankers do not exert themselves to reduce as many countries as possible to the condition of Greece and Egypt, wherein the bankers’ trust, as a guarantee of debts, seize upon state revenues or state properties. As if the Russian looters would scruple to pawn state railways, mines, the liquor monopoly, etc.

ciples on the 4th of August: “Feudal rights abolished!” In reality, it was mere verbal fireworks, but the peasants, consciously confounding declaration with law, refused to pay all feudal dues.

No doubt, those were mere words, but they stirred revolutions.

Finally, there was more than mere words, for, availing themselves of the government’s perplexity, the French deputies boldly attacked the antiquated local institutions, substituting for the squires and magistrates communal and urban municipalities, which subsequently became the bulwarks of the revolution.

“Different times, different conditions,” we are told. Indisputably so. But the illusions precluded a clear realization of the actual conditions in Russia. Our deputies and politicians were so hypnotized by the very words “popular representatives,” and so far underestimated the strength of the old regime that no one asked the pertinent question: “What must the Russian revolution be?” However, not only the believers in the magic .power of the Duma were misguided. Our Anarchist comrades erred in assuming that the heroic efforts of a group of individuals would suffice to demolish the fortress of the old order reared by the centuries. Thousands of heroic exploits were performed, thousands of heroes perished, but the old regime has survived and still does its work of crushing the young and vigorous.

Yes, the era of illusions has terminated. The first attack is repulsed. The second attack should be prepared on a broader basis and with a fuller understanding of the foe’s strength. There can be no revolution without the participation of the masses, and all efforts should be directed toward rousing the people who alone are capable of paralyzing the armies of the old world and capturing its strongholds.

We must forge ahead with this work in every part, nook, and corner of Russia. Enough of illusions, enough of reliance on the Duma or on a handful of heroic redeemers! It is necessary to put the masses forward directly for the great work of general reconstruction. But the masses will enter the struggle only in the name of their direct fundamental needs.

The land—to the tiller; the factories, mills, railways— to the worker; everywhere, a free revolutionary commune working out its own salvation at home, not through representatives or officials in St. Petersburg.

Such should be the motive of the second period of the revolution upon which Russia is entering.

This Article first appeared in The Nineteenth Century Vol 13. No, 75 January 1883

It is pretty generally recognised in Europe, that all together our penal institutions are very far from being what they ought to be, and no better indeed than so many contradictions in the action of the modern theory of the treatment of criminals. The principle of the lex talionia—of the right of the community to avenge itself on the criminal—is no longer admissible. We. have come to an understanding that society at large is responsible for the vices that grow in it, even as it has its share in the glory of its heroes; and we generally admit, at least in theory, that when we deprive a criminal of his liberty, it is to purify and improve him. But we know how hideously at variance with the ideal the reality is. The murderer is simply handed over to the hangman; and the man who is shut up in a prison is so far from being bettered by the change, that he comes out more resolutely the foe of society than he was when he went in. Subjection, on disgraceful terms, to a humiliating work gives him an antipathy to all kinds of labour. After suffering every sort of humiliation at the instance of those whose lives are lived in immunity from the peculiar conditions which bring man to crime—or to such sorts of it as are punishable by the operations of the law—he learns to hate the section of society to which his humiliation belongs, and proves his hatred by new offences against it. And if the penal institutions of Western Europe have failed thus completely to realise the ambition on which they justify their existence, what shall we say of the penal institutions of Russia? The incredible duration of preliminary detention; the horrible circumstances of prison life; the congregation of hundreds of prisoners into dirty and small chambers; the flagrant immorality of a corps of gaolers who are practically omnipotent, whose whole function is to terrorise and oppress, and who rob their charges of the few coppers doled out to them by the State; the want of labour and the total absence of all that contributes to the moral welfare of man; the cynical contempt of human dignity, and the physical degradation of prisoners—these are the elements of prison life in Russia. Not that the principles of Russian penal institutions were worse than those applied to the same institutions in Western Europe. I am rather inclined to hold the contrary. Surely, it is less degrading for the convict to be employed in useful work in Siberia than to spend his life in picking oakum, or in climbing the steps of a wheel; and—to compare two evils—it is more humane to employ the assassin as a labourer in a gold mine and, after a few years, make a free settler of him, than peaceably to turn him over to a hangman. In Russia, however, principles are always ruined in the application. And if we consider the Russian prisons and penal settlements, not as they ought to be according to the law, but as they are in reality, we can do no less than recognise, with all the best Russian explorers of our prisons, that they are an outrage on humanity.

In England and in the United States several attempts have recently been made to represent the Russian prisons under the most smiling aspect. The best known of them are those made by the Reverend Mr Lansdell in England, and by Mr Kennan in the United States. Mr Kennan came to the conclusion that his sojourn as an officer of the Overland Telegraph Company on the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk—a few thousand miles, more or less, from the penal quarters of Siberia—entitles him to speak authoritatively about Siberian prisons and prisoners. Is it surprising that his experience should be flatly contradicted by those Russians who have seriously studied the life of prisoners in Siberia? Of Mr Lansdell there is something more to say. He has seen Siberian gaols. Outstripping the post in his career, he has crossed a country which has no railways, at a speed of 6,300 miles in 75 days; and in the space of fourteen hours, indeed, he breakfasted, he dined, he travelled over 40 miles, and he visited the three chief gaols of Siberia—at Tobolsk, at Alexandrovskiy Zavod, and at Kara. Amply furnished with official recommendations, he saw, during this short time, as much as the officials chose to show; and for a country like Siberia that is surely a great deal. Had he anything of the critical faculty which is the first virtue of a traveller, it would have enabled him to appreciate the relative value of the information he obtained in the course of his official scamper through the Siberian prisons, and his book— especially if he had taken note of existing Russian literature on the subject—might have been a useful one. Unhappily, he neither saw nor read, and his book—in so far, at least, as it is concerned with gaols and convicts—can only convey false ideas. This being the case, I think the present paper may prove of interest. Such information as it contains is, at least, authentic, inasmuch as it is derived, not only from books but from the personal experience of prison life of myself and certain of my friends.